A little piece by BBC South East about the fight against plastic pollution and the messages in bottles I find whilst collecting plastic in Kent along the Thames Estuary and the River Medway.

|

3 Comments

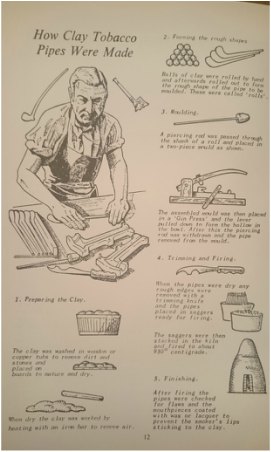

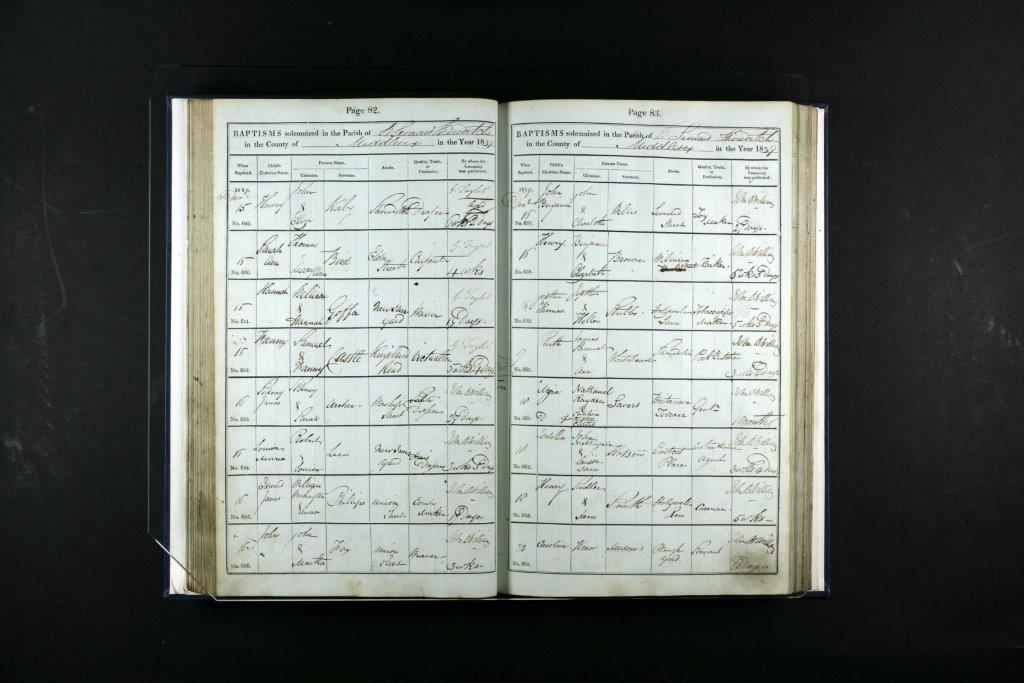

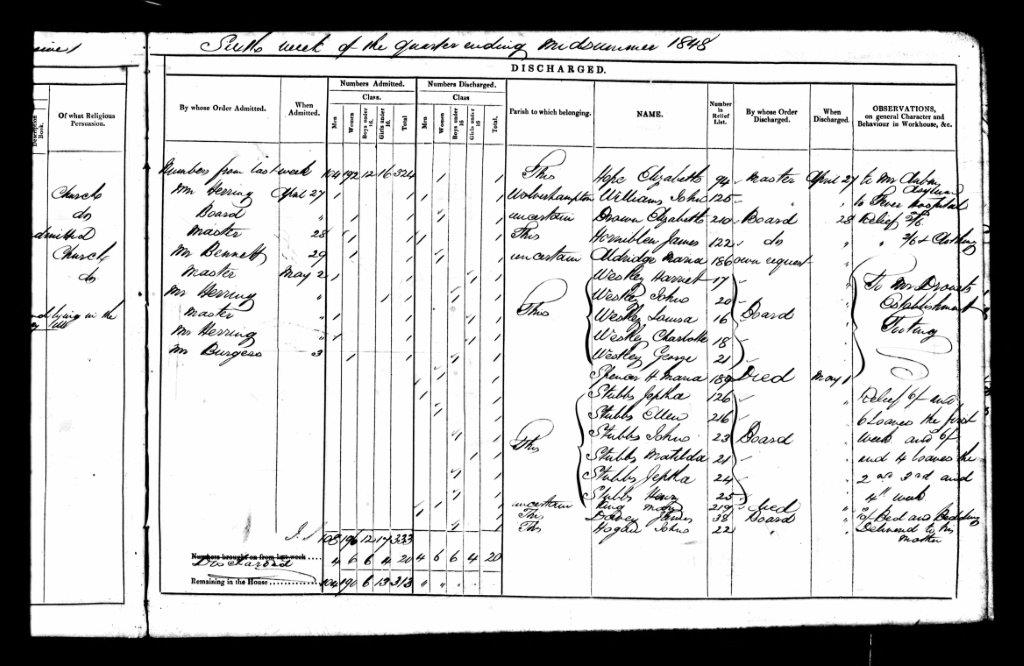

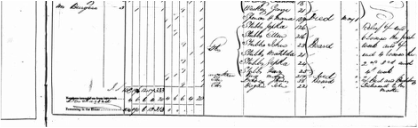

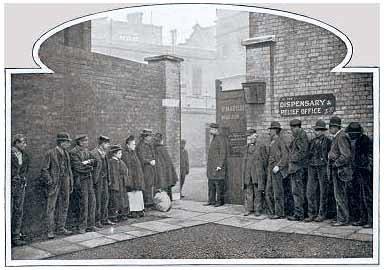

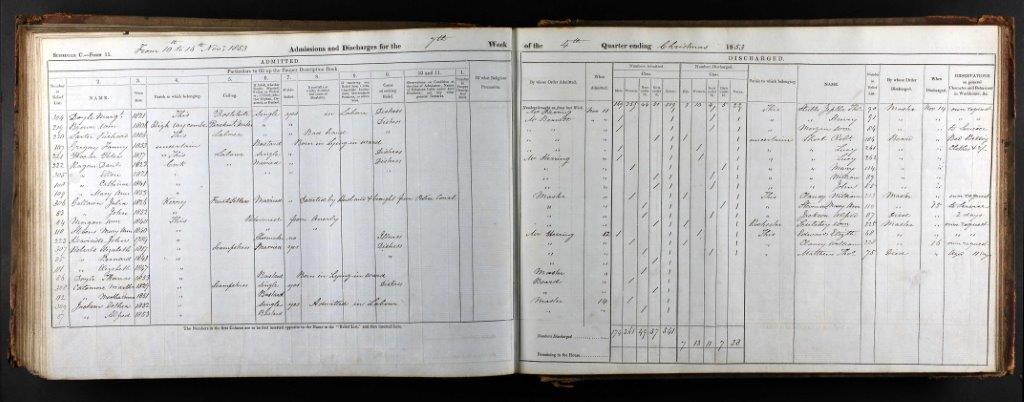

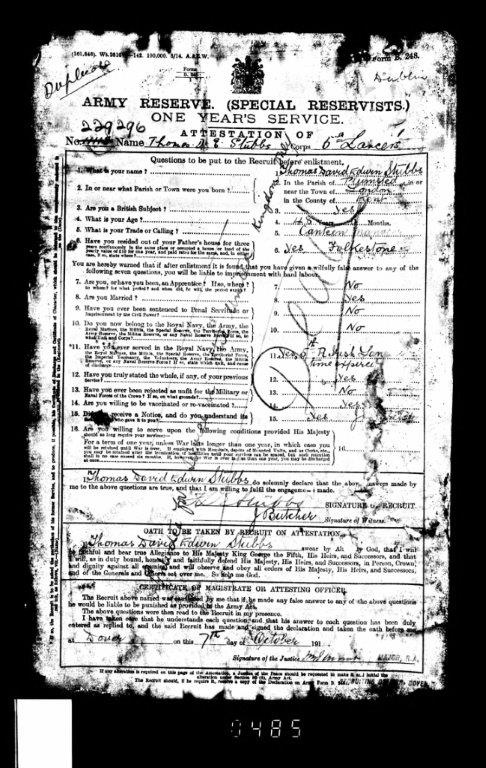

Fragments of past lives are scattered over the beaches of the River Thames in London, be that in the family business name engraved on a brass button, the crest on a piece of pottery, or in this case, a name stamped on a clay pipe stem. And when you hold a river worn piece of history bearing a name, it holds the potential to bring back a story from the past, or indeed a whole family. This pipe stem did just that. It not only lead me to discover a family of clay pipe makers from Plumstead, but also, it lead me where I was not quite expecting to go; to Christ Church workhouse in Southwark in 1847. It is very common to find clay pipes on the Thames foreshore, and it is especially common to find pipe stems. It’s great to find an actual bowl, or even better a whole pipe. Even a stem though can give a lot of clues as to its origin, especially if it has a makers mark on it, or the name of the pipe maker. In approximately 1860, it became common practice to put the maker's name on the side of the stem, and the name of the town in which he worked on the other side. It is of course particularly exciting to find evidence of a local person, and the pipe stem pictured above was just that. I found it on the Woolwich foreshore, and it originated just down the road, in Plumstead. It was a couple of weeks ago that I stooped to pick up a clay pipe stem and noticed it had the name “T. Stubbs” engraved on it. And on the other side, Plumstead. I googled the name "T. Stubbs", and I was delighted to find that it turns out that it is a clay pipe almost certainly made by Thomas Jeptha Stubbs, who was born in 1840 in Shoreditch and who by 1861 was a tobacco pipe manufacturer living at Princes Road in Plumstead. This was great news, as I have occasionally found pipe stems with names on them, and I have been unable to find any information whatsoever. With the amazing wealth of information at our fingertips these days, I was then able to find out through the ancestry research website, that Thomas Jeptha Stubbs married Elizabeth Farlie of Tilbury and went on to have 9 children with her. They married in 1861 in Greenwich when they were both in their very early twenties. At least three of their children also went on to become pipe makers. Princes Road, where they lived, is no longer in existence, but it seems that quite a few members of the Stubbs family lived there, including Thomas’s brother Henry Stubbs and also his mother Ellen, who had been widowed twice by 1881. Members of the family were often involved in the manufacturing of the clay pipes, which might explain why the Stubbs children became pipemakers themselves (Thomas, Henry and Walter), after helping their father Thomas Jeptha Stubbs in his workshop. It was common for women and children between 12 and 15 years old to help with the moulding of pipes. Here below is also some of the ways that they may have helped in the pipe making process. So let's go back to the beginning, to when Thomas Jeptha Stubbs was born in circa 1839 to Jeptha and Ellen Stubbs. He had 4 other siblings, and his brother Henry also went on to become a clay pipemaker. He was baptised in 1839 at Saint Leonard's Church, Shoreditch. Baptism record below. Thomas Jeptha Stubb’s father was also called Jeptha and was born in 1797. His vocation was also recorded as being a clay pipe manufacturer. It seems though that life was certainly not easy for Jeptha senior, and his wife Ellen – and according to records, the family made frequent trips to the Christ Church Workhouse in Southwark where they were admitted on 3 or 4 occasions between the years 1847 and 1854 and were provided with food and shelter. It has to be mentioned that a lot of pipemakers struggled to make a living. This was for a variety of reasons, but especially as there was such a lot of competition. By 1650 there were at least a thousand pipe makers in London alone and many others operating in other towns. It was not unusual for pipemakers to travel from town to town to escape this extreme competition. Also, there were issues such as availability of fuel for firing, and the distribution of pipes. There was also the fact that innkeepers cleaned pipes so that they could be used over and over again by their customers and this didn't help pipemakers desperate to sell their wares. I wonder therefore, if any of these problems were encountered by Thomas's father Jeptha - which may have caused him to seek help from the Christ Church workhouse (who provided relief to the poor in times of hardship). Life would not have been particularly easy or family oriented in the workhouse, and so it is evident that they stayed only as long as necessary to get back on their feet again by the looks of it and it’s clear that Jeptha Stubbs did not want to stay longer than necessary as he discharged them from the workhouse on several occasions. The records from the Christ Church workhouse below detail how the family were given loaves of bread and other help, during their stay. Other records on the Ancestry site show that the whole family were admitted together on several occasions. This would not have been a lot of fun, as families were not generally able to stay together. There is an excellent source of information about Victorian workhouses at http://www.workhouses.org.uk/StSaviour/ where you can get an idea of how life would have been in a workhouse in 1847. The Stubbs family were admitted into the workhouse not long after the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. This law ensured that no able-bodied person could get poor relief unless they went to live in special workhouses. The idea was that the poor were helped to support themselves. They had to work for their food and accommodation. On the plus side, a workhouse provided:

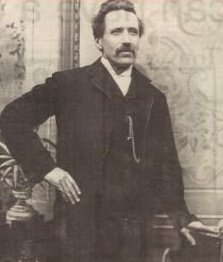

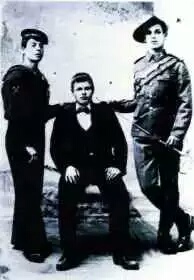

The workhouse was not, however, a prison. People could, in principle, leave whenever they wished, for example when work became available locally. Some people, known as the "ins and outs", entered and left quite frequently, treating the workhouse almost like a guest-house, albeit one with the most basic of facilities. For some, however, their stay in the workhouse would be for the rest of their lives. The Christ Church workhouse in Southwark where Jeptha, Ellen and young Thomas Jeptha Stubbs stayed (along with his siblings) was almost certainly the Marlborough Street workhouse, which was designed by George Allen and was erected on St Saviour's Marlborough Street site in around 1834, just predating the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. It stood within the parish boundaries of Christ Church, and so was often referred to as the Christ Church (or Christchurch) workhouhouse. It's quite sad to note that the last discharge records for the Stubbs family, from Christ Church are in November 1853, when Thomas Jeptha Stubbs and his brother Henry discharge themselves 11 months after their father Jeptha dies whilst a resident in the workhouse at the approximate young age of 54. He was buried on January 7th 1853 at St Peters Church, Walworth (Southwark). This means that Thomas and Henry would have been teenagers when they discharged themselves (about 15/16 years old). And happily, it seems they never went back. At least, there are no records to indicate that they did. At some point after that, both Thomas Jeptha Stubbs and his brother Henry, ended up in Plumstead making clay pipes and having their own families. We know that Thomas Jeptha Stubbs married Elizabeth in 1661, and by 1881 they were living at 22 Princes Road with several children (who were helping him with the pipe making). His brother Henry Stubbs was living at 31 Princes Road with their by now twice widowed mother, Ellen. Their lives were doubtless not always easy either. One of their 9 children died in combat in the first world war (Thomas David Edwin Stubbs). He was in the special reservists (The Reserve Cavalry Regiment. 1st Battalion). He died on 5th September 1918 and he is buried in Curragh military cemetery in Ireland. The picture of the grave below is that of Thomas David Edwin Stubbs 11118 Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant, The Reserve Cavalry Regiment. 1st Battalion. (Transferred to 229296 The Labour Corps. Son of Thomas Jeptha Stubbs. Husband of Mabel Stubbs, of Folkestone). Thomas Jeptha Stubbs himself, died in 1912, well before the first world war in fact, in Lewisham, at the age of 72. And now, jumping forward to the 21st century, I hope that Thomas Jeptha Stubb’s great grandson will not mind me giving him a mention. Mr B. Stubbs who owns Tavern Snacks based in Charlton (and who kindly allowed me to use the photograph of his great grandfather Thomas Jeptha Stubbs), has said this of him: “Thomas Jeptha Stubbs, manufactured and delivered clay pipes to public houses in the East and South East London by horse and cart. Today pipes have been replaced by snack foods & vehicles are no longer horse drawn” Even though it was initially Thomas Jeptha Stubbs and his Plumstead pipe making business that intrigued me, through sheer virtue of finding one of his pipe stems that he himself (or one of his children) would have stamped, I have to admit, that by the end of my research, my thoughts were especially with Thomas's father, Jeptha Stubbs who last saw his sons Thomas and Henry when they were teenagers, and who died unaware that they were to go on to have large families and successful businesses, right up to the present day. I am so glad that I found this name stamped on a clay pipe stem during one of my Woolwich mudlarking trips. It is another of the stories that the River Thames throws out with the tide - and it goes to show that your story, and your name lives on long after you are gone. Here's a special shout out to Jeptha Stubbs, who looked after his family in the best possible way that he could, and must have done a good job, as it seems they did pretty well - God rest his soul - I have no doubt that he would be exceptionally proud of them all. Credits for this post go to the following : Mr B. Stubbs - Tavern Snacks Ancestry.co.uk Eric G Ayto - Clay Tobacco Pipes www.workhouses.org.uk Warren - Tavern Snacks

** If you have enjoyed reading this, you may also enjoy reading about Frederick Jury, a World War One soldier, whose luggage tag I found in the Thames mud, in August 2015. http://www.tidelineart.com/tideline-art-blog/a-river-thames-mudlarking-find-brings-to-life-world-war-one-soldier-frederick-jury-1873-1932 2000 - October 15th 2015 Last night, Mischa, much loved labrador and family member drew her last breath. She was fifteen years old and lived her life to the full. Only on Sunday she was wading through the Thames estuary mud like Lassie on a rescue mission. I felt compelled to write a little eulogy for her. She wasn't my dog, but I met her five years ago and since then, I grew to love her very deeply. Fearless girl, she traipsed through knee deep mud in search of mudlarking treasures, she braved the perilous currents of the River Thames to retrieve bottles and balls. She loved nothing more than to throw herself into the Thames estuary, to search and bring back whatever you threw in. She found my first ever message in a bottle out of 70. She frolicked with a seal called Judo, and she captured the hearts of many a passerby. With a penchant for food, she hoovered up the Cutty Sark pub floor in Greenwich with great efficacity. She didn't have a bad bone in her body and I thank her deeply for the times we spent with her. It will feel very odd walking along the Thames Estuary without her, and I will always think about her when I'm walking along the foreshore of the River Thames. God bless you Mischa. ...Mischa, Thames mud socks Empty plastic bottles ...must retrieve them... bacon sandwich corners - please paw... nudder one... Stinkum walkies Get out of the paddy water Mischa Where's the bunny rabbit? Where's the birdies? Wheres your toy gone? Over there where the sunlight streams through the clouds like gold. Where the Thames estuary embers meet the sky's fiery blaze There it is. Go fetch. Bed with it. Flame on Mischa, Flame on. Mischa and Judo the Seal in the River Thames Greenwich, 2013 In memory of a lovely companion.

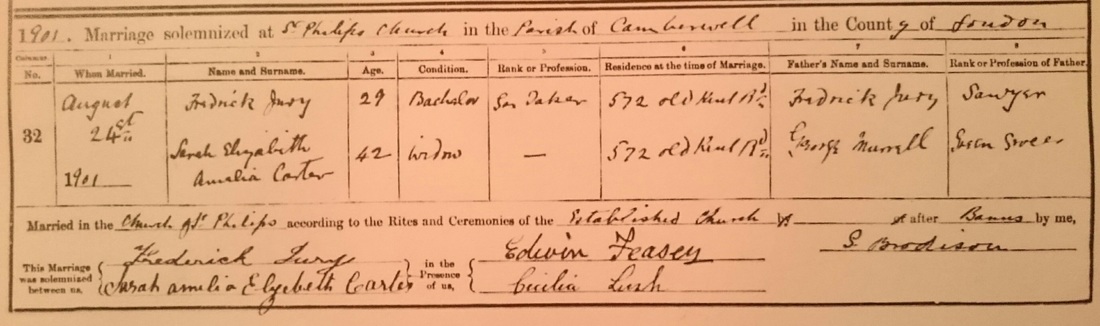

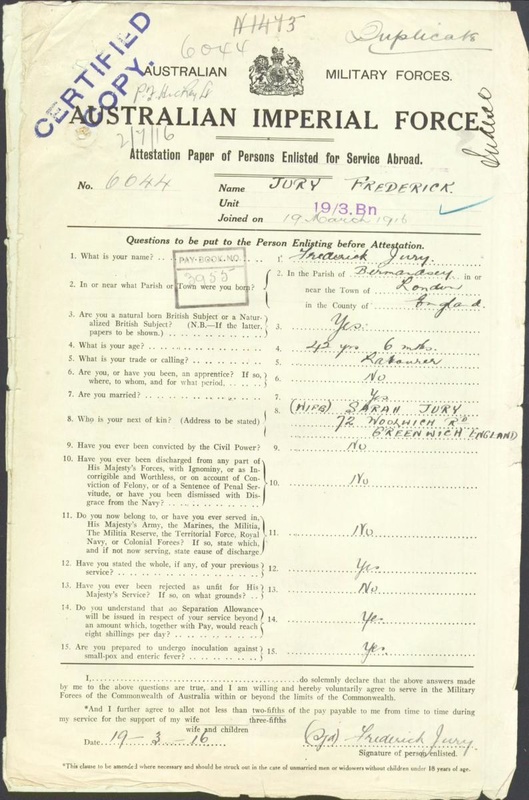

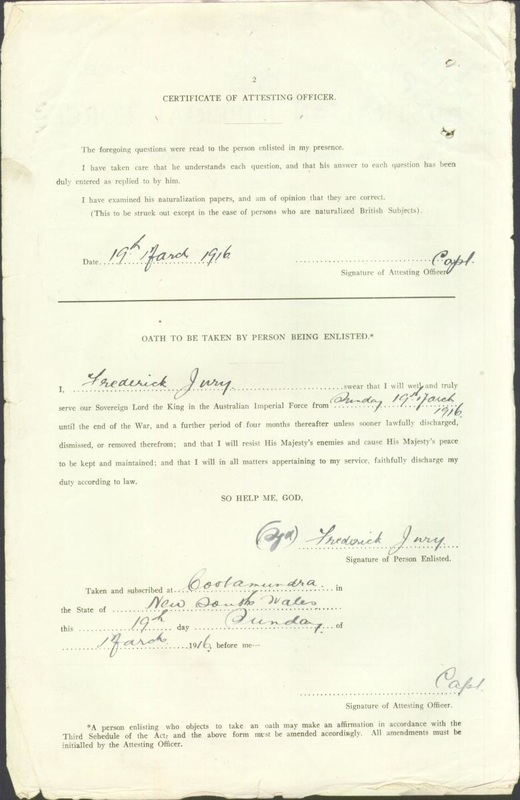

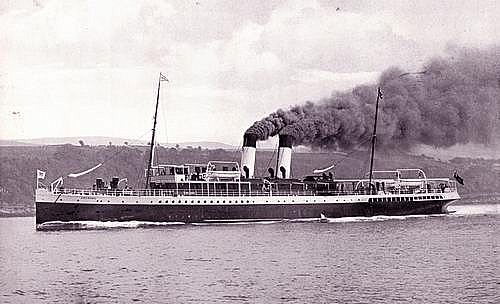

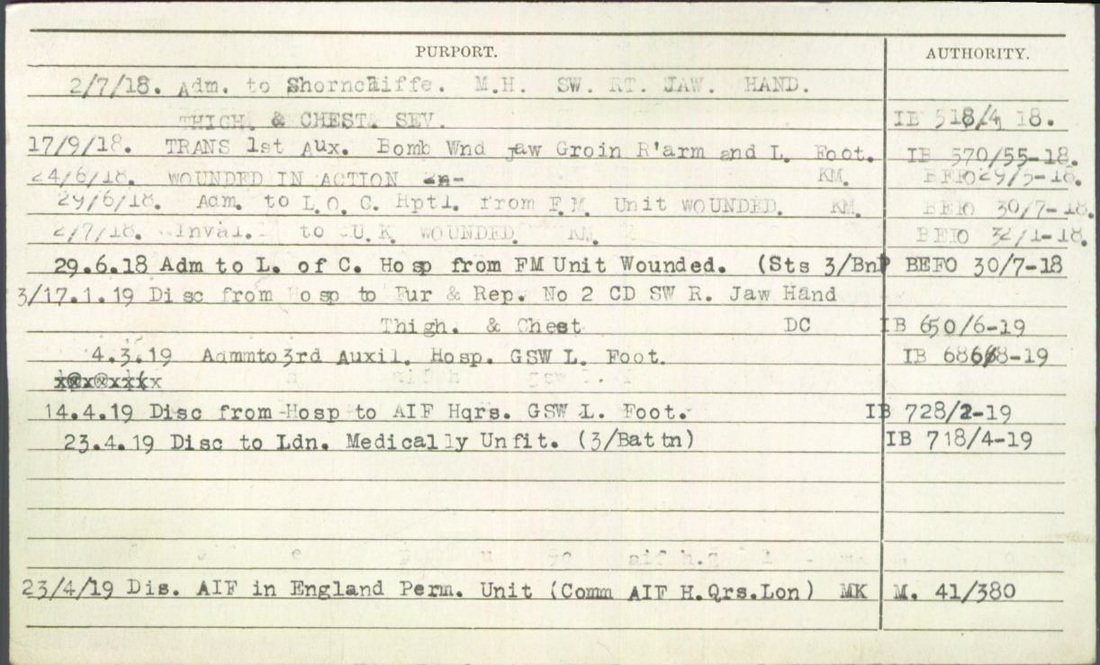

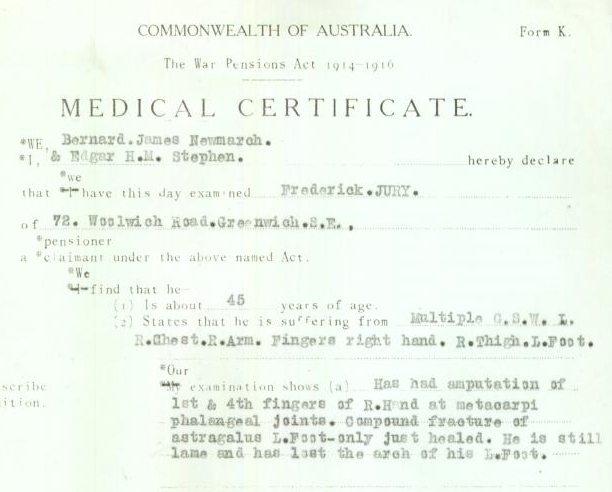

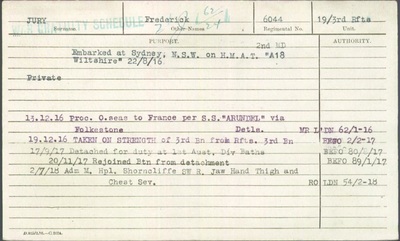

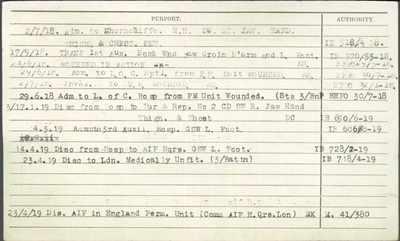

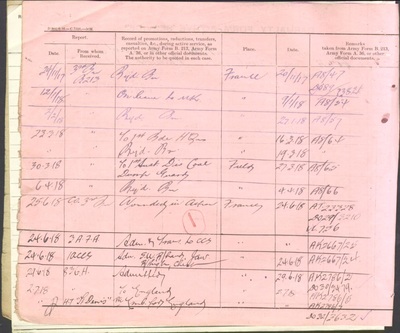

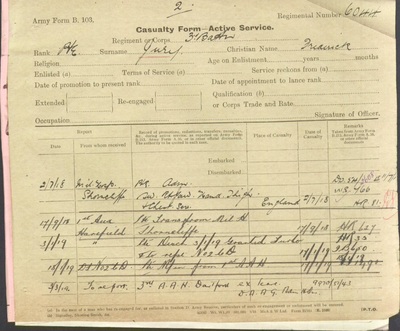

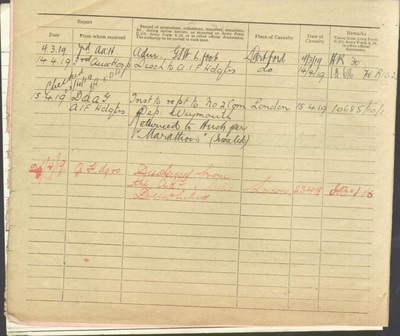

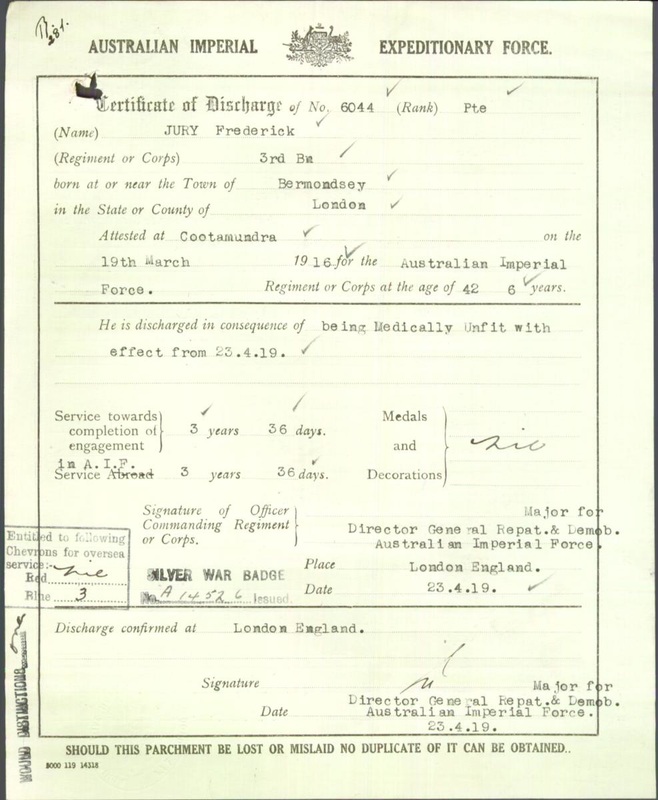

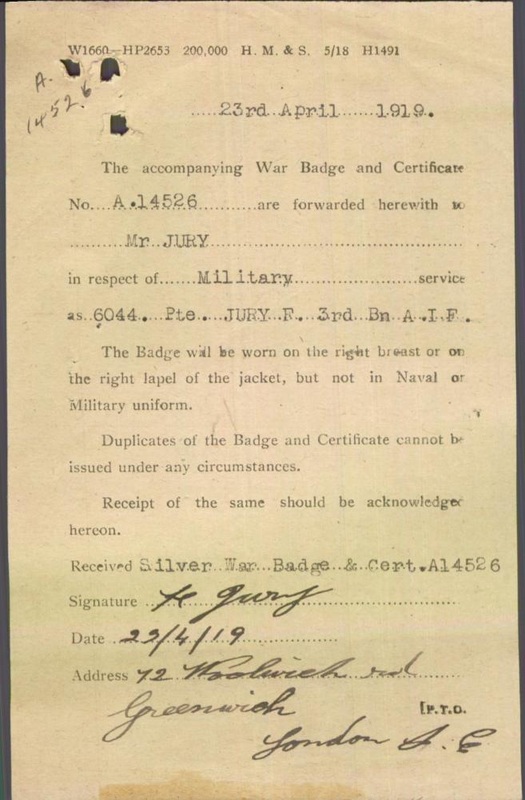

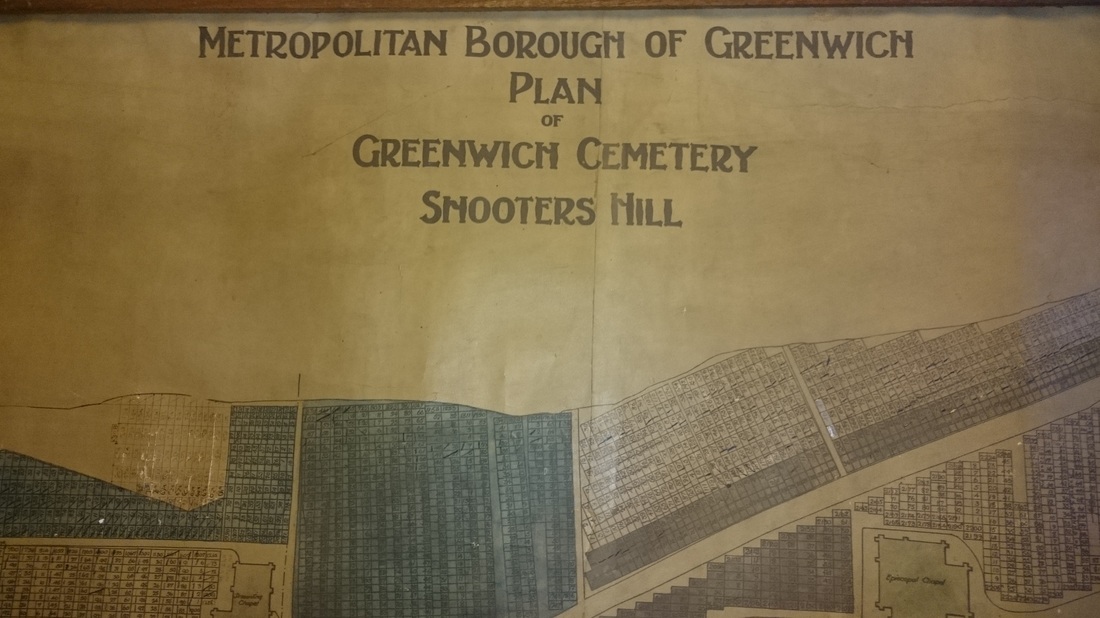

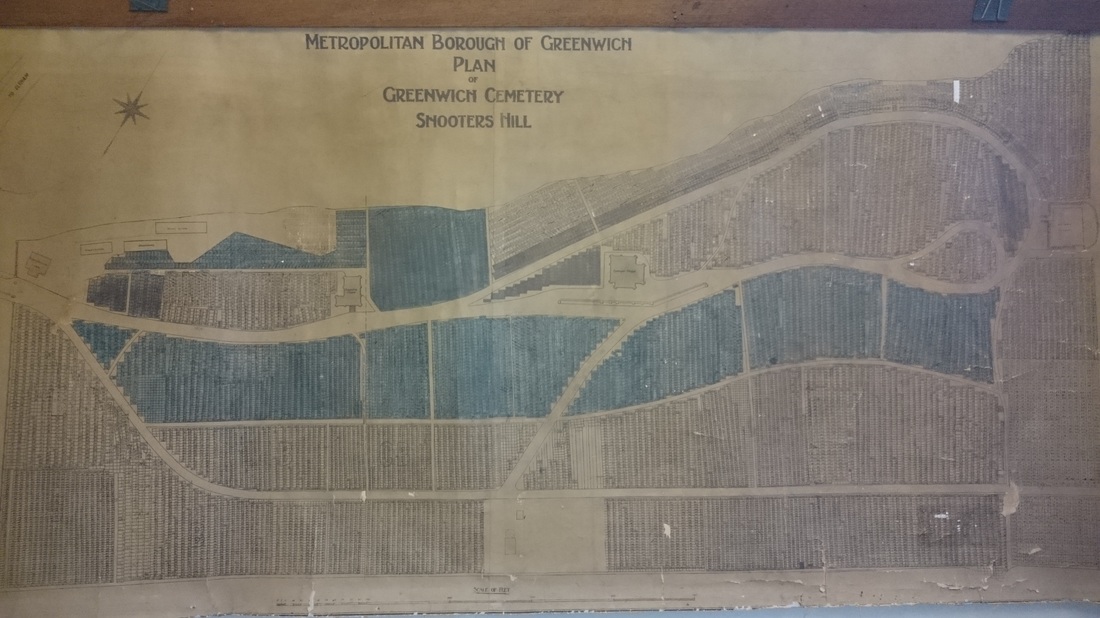

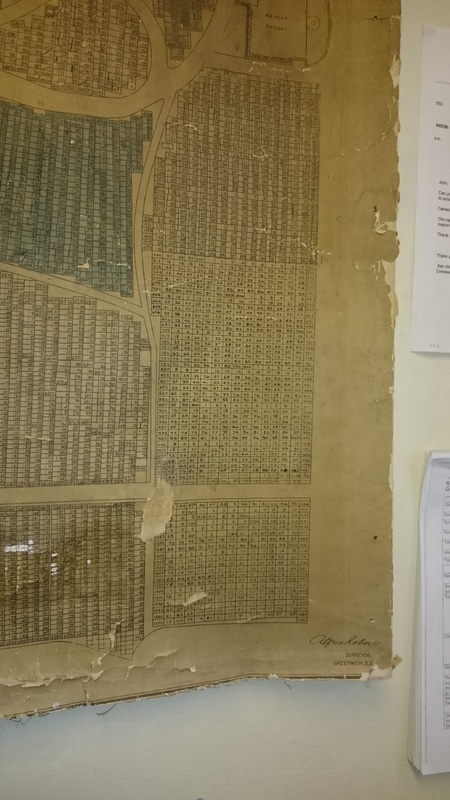

We'll never forget you Mischa. a river thames mudlarking find brings to life world war one soldier, Frederick jURY (1873 - 1932)5/9/2015 On 22nd August 2016, it will be exactly 100 years since Frederick Jury (Private no. 6044, 3rd infantry Battalion, 19th Reinforcement, in the Australian Imperial Forces) embarked from Australia on the ship HMAT A18 Wiltshire from Sydney to travel to France via Folkestone, to fight in the First World War. How did the story of Frederick Jury come to light? A simple Thames mudlarking find last week one evening after work in Greenwich, London, on Thursday 27th August 2015. A small, piece of metal s0 insignificant I almost passed it by as a piece of shrapnel, but then I noticed through the mud and drizzly rain, an engraved name, “F. Jury", and a faded address. I popped it in my bag for closer examination later that evening. Perhaps it was a shop in Woolwich I thought. On returning home, I cleaned it off and the engraving was revealed to be "F. Jury, 72 Woolwich Road, SE" The SE would stand for South East London. 72 Woolwich Road is in Greenwich, SE10. Occasionally, a seemingly innocuous find in the River Thames such as this, can be compared to opening up a glorious story book. It is no secret that it is the hidden stories behind the items which I find washed out by the Thames tide, which fuel my passion for mudlarking. With the help of a lot of people on twitter, (after I posted a picture of F. Jury's brass luggage tag last Thursday 27th August), I was to find that this small, muddy object was to conjure up a whole family of people from the past, with their lives opening up before me like an intriguing novel. These people and their very real dilemmas have lain forgotten for years (especially in this case, as there seems to be no living close relatives). So here is a brief outline of the very worthy life of Frederick Jury, the owner of the luggage tag, discovered in the Thames mud on 27th August 2015 at Enderby Wharf Greenwich. I have had some wonderful help with the research about Fred and his family, and I would not have been able to write this blog about him without the invaluable help of a number of people, namely: Deborah O' Boyle @dimblydeb Julia Davis @familyhist2DAY julia.davis@familyhistorytoday.co.uk Clay Harris @mudlarklives John Layt @odysseus_nz www.layt.net/john Rob Powell of @greenwichcouk @catford_cat @hp88 @London_Mush Jason - Gravedigger at Greenwich Cemetery The National Archives of Australia http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au And I bet I forgot someone so please let me know if I did forget you!! The Story of Frederick Jury of 72 Woolwich Road SE10, 1873-1932 Frederick Jury was born in Bermondsey/Southwark in 1873 to Frederick and Julia Jury. Records show that he grew up in Maidstone and Aylesford, and that his parents, (his father also called Frederick (first a labourer and then a sawyer)) and Julia were from Maidstone and Aylesford respectively. We know from research that he had a brother called William Jury, a Seaman, who was considerably younger than he was (born in 1891). We don't know anything about Fred's childhood, but we do know that by 1900/01 he was a Gas Stoker, and he was renting a first floor furnished room at Sarah Amelia Elizabeth Carter's house at 572 Old Kent Road (1901 electoral register). The 1901 census reveals that Sarah Carter was running a coffee house there and that she herself was born in Newington in approx 1860. A bit about Sarah now who was to play a significant part in Fred's life. Sarah's father was called George Murrell and he was a greengrocer. She was married to James Carter on 27th March 1882 at the age of 22, and they had 2 children, Augustus James Carter (in 1883) and William Carter (born circa 1885). Sadly, her husband James died sometime after 1895. It seems that Fred and Sarah fell in love, and on 24th August 1901, Fred and Sarah got married, at St Philip the Apostle Church, Avondale Square. Sarah was 13 years older than Fred and was 42 when they married. He was 29. One interesting point to note is that one of the witnesses is a Ms Cecilia Lush (and Cecilia goes on to marry Augustus Carter, Sarah's son and Fred's stepson). I have to say that quite aside from everything else, I absolutely love the name Cecilia Lush! (If I ever change my name, I will most definitely call myself that). Sarah and Fred never did have any children of their own. So where does 72 Woolwich Road come into it which is the address engraved on the brass luggage tag that I found on the Thames foreshore on Thursday 27th August? According to the 1904 electoral register, Fred was living at 72 Woolwich Road in 1904, and the 1911 census shows that Fred and Sarah are living there together. It would appear that Sarah was again running a coffee house from there. I love to imagine the people who might have come to buy a coffee from her at that time in Greenwich - and the conversations they might have had. There was also a boarder living at 72 Woolwich Road, William Sullivan, who was a brick layer. As a mudlark, I come across so many types of different vintage bricks, especially in Greenwich. I wonder if William Sullivan touched any of them. There seem to be rather a lot of Williams around at that time. Fred's brother was also a William and so was Sarah's son from her first marriage! The picture below is 72 Woolwich Road as it is today, just to the right of the Solicitors office.  72 Woolwich Road, Greenwich, where Fred Jury lived with his wife Sarah from 1904 at least 72 Woolwich Road, Greenwich, where Fred Jury lived with his wife Sarah from 1904 at least We can only assume that life continued on at 72 Woolwich Road happily until 1914 and the outbreak of World War 1. It would appear that both Frederick Jury and his brother William Jury, enlisted into the Australian Imperial Forces within one month of each other. William Jury enlisted age 25 on 3rd March 1916 and Frederick enlisted on 19th March 1916 aged 42 years. Was Frederick pursuing his younger brother for some reason? This and much of the following information we know from the extensive Austrialian Imperial Forces war records to be found online. Why did they go to Australia to enlist? Well we don't know why, but it could perhaps be that the pay was apparently 3 times as much as the British Army, and in Fred's case it could have been that he was too old to enlist at home (and the upper age limit was higher in Australia). All this is of course just speculation. Maybe Fred wanted to protect his brother William. We do know that in all probability Fred travelled to Melbourne where he enlists at Cootramundra in New South Wales. Sarah we believe stayed in Greenwich, at 72 Woolwich Road, during this time. Then, on 22nd August 1916, almost 15 years to the day that he and Sarah were married, he embarked from Sydney, Australia to the UK on the ship HMAT Wiltshire. He then proceeded overseas from Folkestone to France on the SS Arundel in December 1916 to fight on the Western Front. Fred fought with the Australian Imperial Forces 3rd infantry battalion, 19th reinforcement. The 3rd infantry battalion were sent to France to fight on the Western Front in 1916. For the next two and a half years the unit would serve in the trenches in France and Belgium and would take part in many of the major battles fought during that time. (In May 1919, following the end of the war, the battalion was disbanded and its personnel repatriated back to Australia). We can see from Fred's records that he saw active service in Meteren France, and it was here that he was severely wounded on several occasions; notably in March 1918 when he was hit by a stick bomb, which fractured his left foot, and then on 24th June 1918 he was hit by a grenade thrown at close range. I can only begin to imagine how terrifying it must have been. Fred received significant injuries to his chest, jaw, arm, finger, thigh and foot. He then had several fingers amputated as a result of his injuries, and received major injuries to his left foot. Some of the records are below. In June of this year, I found an unexploded world war II hand grenade very close to where I found Fred's luggage tag, near Enderby Wharf in Greenwich. The controlled explosion was enough to cause a stir in Greenwich, so imagine having one thrown right at you - in a very "uncontrolled" kind of way?! Terrifying. This must have been a worrying time for Sarah his wife too who must have been waiting to hear the worst at any moment. It is worth mentioning that during the course of its involvement in the war, the AIF 3rd Battalion suffered 3,598 casualties, of which 1,312 were killed in action The photos below are groups of Australian Imperial Forces soldiers, taken at Meteren in 1916. As a result of his injuries, Fred spent time in two military hospitals, The Harefield Hospital in the London borough of Hillingdon, and the Military Hospital, Shorncliffe, Kent. Fingers were amputated at Shorncliffe. Harefield Hospital was used as an Australian military hospital during World War One. It is here that Fred first had his foot operated on after it was hit by a stick bomb. Finally, after many operations on his foot, and the amputation of his fingers, Fred was medically assessed as 100% disabled and was discharged from the Australian Imperial Expeditionary Force in London on 23rd April 1919. He had served 3 years and 36 days. When he was discharged from the AIF, Frederick Jury received a "silver war badge". According to Wikipedia, the Silver War Badge was issued in the UK to service personnel who had been honourably discharged due to wounds or sickness during World War 1. The badge, sometimes known as the Discharge Badge, Wound Badge or Services Rendered Badge, was first issued in September 1916, along with an official certificate of entitlement.The sterling silver lapel badge was intended to be worn in civilian clothes. The badge was to be worn on the right breast while in civilian dress, it was forbidden to wear on a military uniform. We know that after World War 1, Fred Jury lived at 72 Woolwich Road and was there at least until the 1931 electoral register. He died on 27th January 1932 at Queen Mary's Hospital Roehampton, which was also a military hospital. Sarah was at 72 Woolwich Road until 1933, but thereafter she appears to have moved to Greenwich South Street, where she died in 1936. As an aside, we also know that Fred's younger brother William Jury enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force just a few months before he did. He was seriously wounded in action, receiving multiple gun shot wounds to the head, and he was committed to Sunnyside Mental Hospital in New Zealand in the 1940s. He died in the 1960s, in the same hospital in New Zealand. He never married and he had no children. Well you might think that that is the end of Frederick Jury's story. However, I thought I would try to find out where he was buried, with the idea that it would be nice to go and pay my respects to him. Well it just so happens that he is buried just around the corner from where I live - in Greenwich Cemetery. After downloading the map location from deceasedonline I made my way to Greenwich Cemetery straight after work, armed with said map, and also accompanied by a friend to help search the gravestones. Well....that is where the fun began, as I drove straight into Greenwich Cemetery (not paying attention to the fact that no cars are allowed - sorry!). Realising we only had 15 minutes to find Fred before the cemetery shut at 7pm, we were on a mission! The sunlight was streaming through the clouds and the view from the Cemetery over London was glorious. However, we had no time for that, as we leapt out of the car at area "Z", and tried to locate Frederick Jury's final resting place from what I realised was a rather vague map. It was like searching for a needle in a haystack, with the added worry that we might end up locked in the cemetery for the night. At 7.01pm we realised we had better head back to the gates, and to our great relief, the gates were not closed and we decided to wait until the gatekeeper came to close them. Sure enough, at 7.05pm precisely, a car sped through the gates and the driver looked at us rather curiously as we got out of the car to greet him. We explained the whole story in a nutshell and the wonderful Jason, grave digger with Royal Greenwich Parks, clearly putting aside the notion that we were quite bonkers, agreed to help us to fulfil our mission of finding Frederick Jury's grave. Well, I have never been in a cemetery office before, and I was overwhelmed to see the beautiful old leather bound books dating back to the early 1800s, with every burial registered within. Jason unfurled a copy of a parchment map of the cemetery so that we could try to pinpoint Fred's grave. And of course, would you believe that there was a big rip in the map, where Fred's grave was located. Still there was nothing for it but to go and search the area. Jason explained that it was in an area reserved for paupers' graves, so there might not even be a stone. Jason kindly agreed to accompany us and help us to search for Fred's grave, and so all three of us set off, aware that dark rainclouds were gathering and the light was fading. The "Z" paupers' area was sadly very overgrown, with small tombstones arranged back to back and in some cases completely covered in brambles and nettles. I wasn't feeling too optimistic to tell you the truth. In some areas you could have done with a machete. And then, after getting entangled many times in nettles and thorns, and peering underneath horizontal gravestones, my friend shouted "I've found Frederick". And so we all went to see him, and Jason straightened the stone. It was a moving moment for me, to see his final resting place, and as Julia Davis from Family History Today quite rightly pointed out, you can only imagine who may have stood there when they buried him all those years ago in 1932. And now of course, there are no relatives left to visit him. Indeed there are no relatives left to visit anyone in area "Z". There was only a rather resplendent fox which seemed to have the "Z" area earmarked as his patch. Here below, is Frederick Jury's final resting place. I was a little concerned when I read "Beloved Husband of Millie Jury" (was this another wife we had not heard of?), but then I was reassured to hear that this was almost certainly a pet name for Sarah Amelia Elizabeth Frances (a shortened version of Amelia). In fact, Sarah's grave is also in Greenwich Cemetery (Zone C) and I plan to seek her in the near future too. Jason the grave digger, my friend & myself spent a few moments next to Fred's grave. It seemed sort of sad that after such an intriguing life, we had to search in the overgrown brambles and grass for his headstone, but Jason, who must be used to such ponderings over the years, said that it really isn't about the material things we leave behind, or the state of the gravestone. It's the legacy we leave, the places we visit, the people we touched in our lives. There must be hundreds and thousands of undiscovered stories lying in the Thames waiting to be found one day. In the case of Frederick Jury, many decades passed before the Thames tide washed away the layers of thick mud to reveal the engraved luggage tag, washing away simultaneously the years until I found myself face to face with Fred and his family. What is this fascination with a stranger from Woolwich who died over 70 years ago? I’ve had to ask myself that. What leads us to take a name on a tag and delve deeper into its history? Maybe it is because none of us want to be forgotten. None of us want to be just a name on a luggage tag that ends up in the River. We want to leave a footprint in the world : for our lives to mean something. That’s how I see it anyway. The good thing is, if you're reading this, you're still alive, and you can still be the author of your own story. So that is the outline of Fred Jury’s life pulled together from the various databases and heritage sites that have information about him. Of course, what we can only imagine, are the real feelings, thoughts and emotions that Fred went through – decisions, considerations, worries, what made him laugh, what made him happy. Why he went to Australia. What he saw when he looked out from the decks of the HMAT Wiltshire. What his dreams were. This brings to mind a quote from a book written by Douglas Kennedy "The Pursuit of Happiness", which I read last year. A quote which really spoke to me. "And do you want to know something rather amusing? My past my choices - when I die, all that past will vanish with me. It's the most astonishing thing about getting old : discovering that all the pain, all the drama, is so completely transitory. You carry it with you. Then, one day, you're gone, and nobody knows about the narrative that was your life. Unless you've told it to somebody or written it down." Douglas Kennedy - The Pursuit of Happiness It’s so true. So I put this to you. If someone found your luggage tag in the Thames in 100 years time, what would they write about you. What is your story? Rest in Peace Frederick Jury.

Gone but by no means forgotten |